What is the “site” of knowledge? Is it a book? A library? An artwork? Or a concept? What is the visual shape or the image of knowledge? And when does a symbol become a pictorial composition, a line drawing, a word or a concept? How do we attach meaning to a line?

Jane Lombard Gallery is pleased to present Sites of Knowledge, a group exhibition curated by the collaborative Re-Sited (Melissa Bianca Amore and William Stover). The exhibition features works by Richard Artschwager, Henri Chopin, Simone Douglas, Guy Laramée, Jen Mazza, Kristin McIver, Enrico Isamu Ōyama, Michael Rakowitz, Karen Schiff and Sophie Tottie. These artists, through various mediums, examine the function of the “symbol” and language per se as their primary apparatus. In many ways, these artists return to the ideologies and techniques once employed by the concrete poets, using linguistic fragments or elements as a structural visual form and as a typographical aesthetic. Their work is about the visual and oral histories of knowledge, and the architecture of memory.

The renowned American artist Richard Artschwager sculpts words and translates perceptions into tangible objects. A former scientist and furniture maker, Artschwager re-contextualizes everyday objects into letters or punctuations suspended in space, creating new form from traditional visual representations of language. The exclamation point featured in the exhibition represents the arbitrary relationship between form and meaning, and reinstates the artist’s dedication to playfully challenging the preconceived associations in language.

French avant-garde pioneer of concrete and sound poetry Henri Chopin’s series of type-writer poems – or dactylopoèmes – represent the possibilities and significance of conveying meaning through visual symmetries, employing text primarily as a concept to be experienced rather than comprehended. During the 1950s, Chopin began experimenting with everyday sounds by recording vibrations and basic movements, creating a series of sound shapes that investigate the psychological relationship between sound and object.

Australian-born artist Simone Douglas’s predominant area of enquiry is with the making of “culture” as a living history and the creation of “language.” Douglas’s work represents the disappearance of oral traditions, storytelling, and the dissolving nature of history and culture. The boat, as a symbolic gesture, emphasizes the mobility of history and the sanctity of oral memories. In the artist’s words, the construction of an ice-ship will serve “as a poetic symbol of reparation – a passionate inducement for considering how we as a nation can go forward.”

French-Canadian artist Guy Laramée retraces the disappearance of the written word by carving and cutting directly into old or used books, creating new topographical landscapes from these discarded pages. Laramée returns to the origin – that is, back to the landscape as a romantic and spiritual gesture. The Grand Library features 80 books from Encyclopedia Britannica and challenges the foundation of knowledge, the work becoming a new “site” of knowledge. Laramée says, “even if the book is dying, even if the paper encyclopedia is gone, the myth of knowledge as an accumulation, the Encyclopedic myth if you like, that myth is far from being dead. We still dream the fiction that knowledge is forever and we dream of keeping it all, all at the same place (be it the web) – and forever.”

The focus of American artist Jen Mazza’s paintings is the concept of “translation” – the translation of ideas and knowledge between languages and from one form to another, as well as what is gained or lost in the process. Mazza sees formal parallels between painting and the book, explaining that “the process of creating the paintings is also a dialogue with form and ideas. Though the finished images are representational, the paintings remain “open,” literally blank, through a great deal of the process. Each image begins as a near abstraction, the book is reduced to its rectangular form placed so as to be somewhat antagonistic to its support (not unlike Malevich’s White on White) with images and text only appearing later in the process.”

Multi-disciplinary artist Kristin McIver examines the vocabulary of social media and the ways in which technology has reshaped the mode of exchange and the employment of language. The artist uses devices including light, language and social media to research “identity” ontology and the disappearance of traditional methods of communication. McIver proposes that ideologies served to consumers through traditional and social media, empowered by advancing technologies and driven by market forces, become referents for new models of self-representation. Her work Indebted to you charts the US national debt figure, recorded at the same time of day over a period of 40 days. The number is so capacious as to become abstract and almost incomprehensible; a figure so large it is never fully visible in its entirety.

The Japanese-Italian artist Enrico Isamu Ōyama is inspired by graffiti, particularly the stylized letters of the writer’s signature, otherwise known as the “tag.” Removing the letter shapes, Oyama keeps only the flowing line and repeats it over and over, exploiting its objectness, and thereby creating an abstract motif or a purely visual object. His works are titled “FFIGURATI, a term referring to the word “graffiti” and the Italian expression “figùrati” (literally translated as “figure it out yourself”). Oyama examines the psychology of attaching “a name” to something or someone, and reveals the significance of language as the foundation to the creation of identity and the ego. The exhibition opening will feature a live painting performance by the artist, in the gallery’s courtyard. While a one-time improvisation, the performance will represent the visual idioms and languages the artist has established throughout his practice.

Using stone quarried from the ruins of a 6th century sandstone Buddha destroyed by the Taliban in 2001, Michael Rakowitz, with the assistance of stone carvers from Afghanistan and Italy, remade books from the State Library of Hesse-Kassel that were destroyed during bombing by the British Royal Air Force in World War II. For Rakowitz, the “undertaking conjures tombstones and recalls the tradition of stone books serving as surrogates for the illiterate.” The project also underscores the notion that though the physical can be destroyed, beliefs, ideas, and knowledge can never be stopped.

Karen Schiff is an artist and wordsmith who often combines both the visual and the verbal into new configurations. Schiff’s drawings, paintings, installations, videos, and performances play with sensory dimensions of language and haptic experiences of space. The Agnes Martin Obituary Project drawings are not just a “thank-you letter” to the woman who has been a major motivating factor in her work, but also a tool for unearthing aesthetics of textual spaces. Staring at Martin’s obituary, Schiff noticed the geometry of the article, as “text columns coalesced with image into an elegant whole. The overall composition gave [her] the feeling of a richly populated spaciousness” both like and unlike Martin’s work.

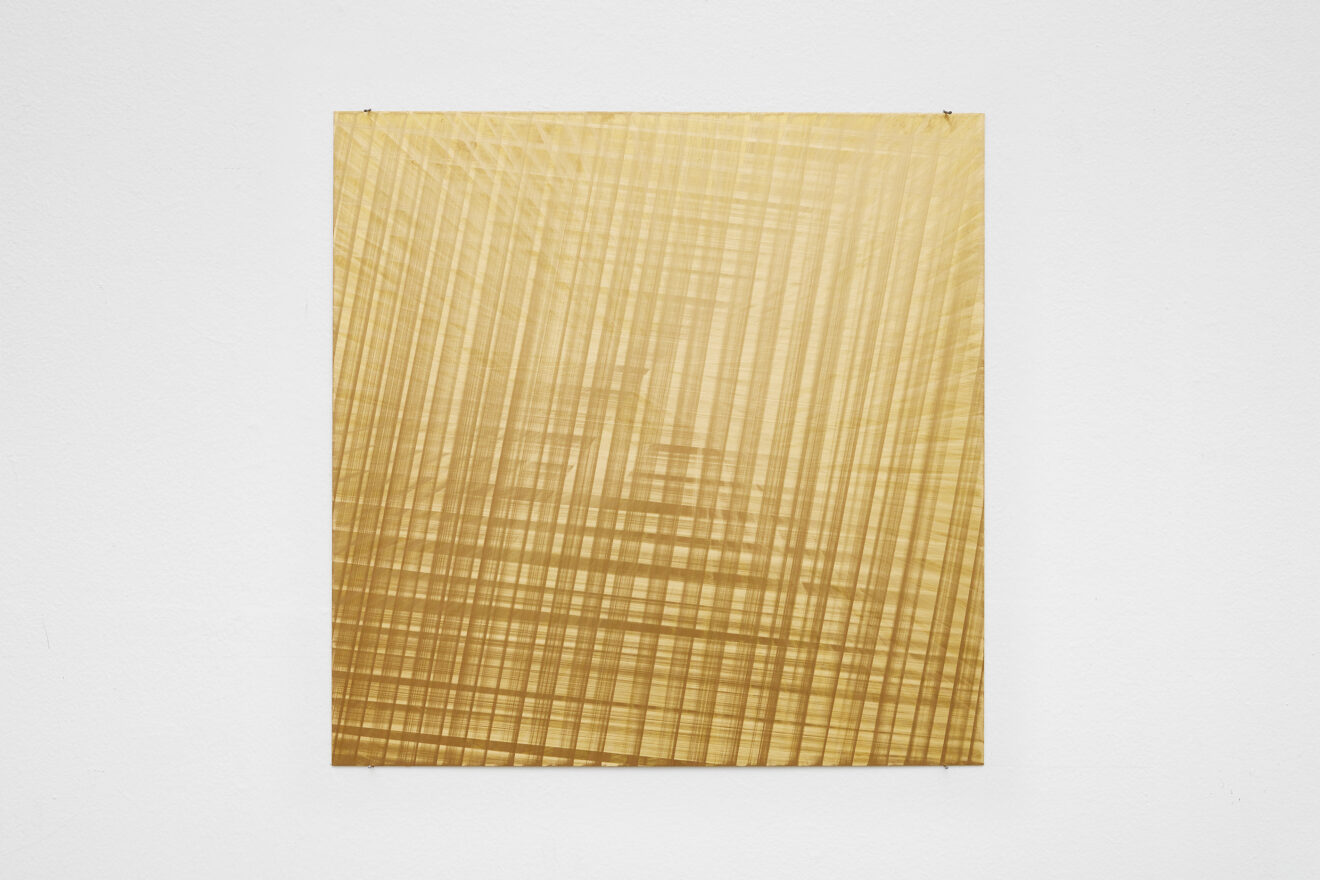

The works of Swedish-born artist Sophie Tottie reveal the physical space between things. The artist employs gestures such as drawing, cutting, and erasing, to examine both the physical presence and the conceptual associations attached to the line. Tottie examines the line as a spatial demarcation, as a thinking apparatus, and as the structural foundation of words and ideas. In her series, Written Language, Tottie illustrates through the activity of meticulous repetitive movements the importance of the line, whether understood as a topography or image, composing a conceptual symphony simply through repetition itself. These works resemble the beginnings of mark making, a place or psychological space that existed prior to comprehension as understood today.

Sites of Knowledge addresses critical ideas about history, authorship and visual structures of knowledge. Indirectly, the curators question how we “look” at knowledge and engage with the complexities of our collective history – both imagined and observed. At what point do we begin to attach meaning to a line, a symmetry, and a sound? Knowledge is primarily understood as the basis to knowing, the basis to creating a network of associations and the relationship between memory and history. So, we will continue to ask: what is the “site” of knowledge?